Tackling Contamination in the Era of E-commerce, China’s Import Ban

Whether its high-speed optical sorters, ballistic separators, non-wrapping screens or robotics, materials recovery facilities are looking to advancements in technology to improve the quality of the materials they process.

It’s no secret that the biggest problem in the fiber end of the market right now is contamination. And that problem has become an even bigger concern over the last 12 months amid the implementation of China’s waste import restrictions.

China has prohibited contaminated exports coming out of materials recovery facilities (MRFs), and as a result, other countries in Southeast Asia like Thailand and Vietnam are implementing their own import bans due to their own capacity problems.

In order to better comply with these demands, MRFs and manufacturers have been looking to advanced developments in technology to improve the materials processed at their facilities, particularly when it comes to source separation and the quality of paper coming out of residential, single stream MRFs. The facilities and their manufacturers are also working to more efficiently handle the effects of e-commerce and major players like Amazon.

Some facilities have implemented high-speed optical sorters, ballistic separators and non-wrapping screens and are updating older, antiquated equipment to properly separate and clean up what comes out of MRFs. Others are using artificial intelligence (AI)—robots—or a combination of technologies. But the general consensus among many is that something needs to be done from a policy and public education standpoint before materials even make their way to the MRFs.

During his time working in the waste and recycling industry, Mark Neitzey, director of sales for Van Dyk Recycling Solutions, has seen the industry change—a lot—notably between 2002 and 2012. MRFs were first built when people were still reading newspapers and recycling simple items, such as bottles, newspapers or cans. But since 2012, the recycling stream has changed drastically, Neitzey points out.

For the equipment installed during 2002-2012, most systems have devices called old newspaper separators—or ONP separators. Or they have something called a news screen, or an ONP screen, explains Neitzey. “So, all these systems have technology to separate newspaper from mixed paper and bottles and cans. Since 2012, the newspaper business dropped off and the Amazon effect has taken over,” he adds.

CP Group’s Felix Hottenstein, optical sorting expert and sales director at MSS, Inc., has noticed the same thing. He explains MRFs used to generate news grade and mixed paper grade, and that the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) is developing new standards and guidelines between old mixed paper grade and new mixed paper grade.

“But in so many of these plants, what’s coming into these streams seems to be getting more contaminated,” explains Hottenstein. “Especially in older sort lines that depend on manual sorting—it’s just not sufficient. They just can’t keep up with too much contamination.”

There are several problems associated with material contamination, but, according to Hottenstein, the education side has always lacked, and educating the public is expensive. Plus, he says, all the new, flexible packaging contaminates the fiber, and that is a challenge now.

In order to remove these contaminations, CP Group has looked to a newer generation of optical sorters.

“The challenge with paper is that there’s a lot of it, and with the optical sorter, you have to be able to spread the material out and present it properly to the machine,” says Hottenstein. “With paper, if you run the machines at your standard speeds like we use for plastic bottles, it’s just not enough. You would need too many machines, and it would get expensive. So, one of the newer technologies for us is that we run the belt twice as fast. That’s one of the main advantages of our fiber-sorting technology and trying to help with the spreading of the materials so the sensors can see what they are actually supposed to sort.”

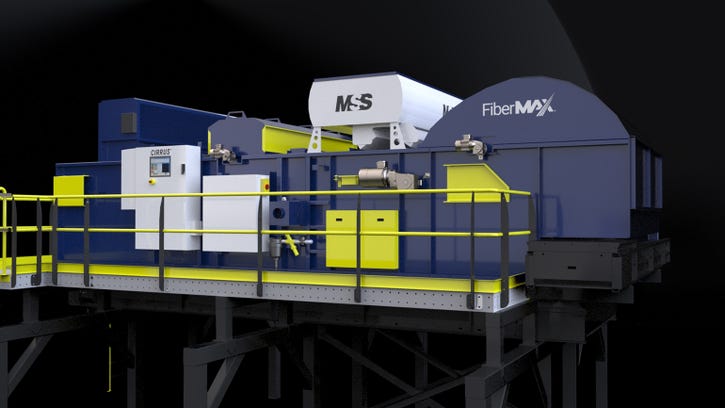

MSS produces optical sorters that run belts at 1,000 feet per minute (fpm) rather than 500 fpm, which is what the company does on the container side, notes Hottenstein. The MSS FiberMAX is what it has been using for its next-gen sorter, and it’s a fairly intricate system.

When lightweight material runs on those high speeds on the belt, it tends to tumble and roll around. So, MSS is using mechanical devices, mostly an air-assist system that helps with moving the air on top of the belt as the same speed as the belt, so the material moves at the same speed.

“The material is fed into the backend of the belt like any optical sorter. But then we have a pinning brush, which is similar to a car wash brush but it touches the belt and pins items that may float around. It pins them to the belt and starts moving them 1,000 feet per minute,” says Hottenstein. “At the same time, we have this flow of air coming down, so the material moves at the same speed as the belt.”

He adds MSS also uses a near infrared spectrometer technology that allows the machine to decipher different materials from each other.

Another problem at MRFs occurs when plastic bags go into the same stream and mix together with all the other products. Those bags end up wrapping around the streaming system, causing hours of downtime because systems have to stop so workers can go in and manually clean the screens.

Neitzey suggests facilities “size separate,” meaning separate by size, and technology can do that using screens. Technology can screen to a certain size, and then facility operators can use optical sorting to positively eject whatever they want ejected.

Van Dyk developed a screen that film bags don't wrap on called a 440 Non-wrapping Screen. Regardless of what it’s fed, the technology will screen by size and angle at the same time.

“What we have customers doing is remove the old screen that wrapped and put in this new screen that didn’t wrap,” says Neitzey. “That has a lot of benefits. Most notably, you don’t have to clean it anymore. Before that screen, you were having to stop the system for four to five hours a day and just cut film bags out of the screen.”

As far as labor and contamination issues in the era of China’s restrictions, Steve Miller, CEO of Bulk Handling Systems, has noticed a similar reaction from MRFs.

“The reaction that most MRFs had to China was to either slow down their lines and add manual labor or avoid the market altogether,” says Miller. “While China led the way in higher-quality standards, most other markets followed suit, although not to the degree that China did. Besides cleaning up material with NIR and color optical sorters, many MRFs are looking to color optical to capture a higher percentage of OCC [old corrugated cardboard] due to the price disparity between OCC and mixed paper.”

E-commerce and the Amazon Effect

When it comes to contamination and the growth of e-commerce and the Amazon effect, Chris Hawn, CEO of Machinex Technologies Inc.’s U.S. division, says the problem is two-fold. Brown contaminants due to the Amazon effect make their way into the fiber stream, which end up downgrading some materials and contaminating the stream. In addition, contaminants from the light-weighted materials sometimes travel with fiber.

Machinex, which designs and manufactures single stream recycling systems and machinery for MRFs, has taken a multipronged approach on how the company ought to address the fiber side of the business and has made new developments to its OCC screen.

“If you look historically at what everyone thinks of as OCC, it was the larger boxes that you see out of distribution or commercial applications,” explains Hawn. “But the Amazon effect has given us much smaller cardboard boxes. When we are separating by size, that smaller box falls through the conventional screens and winds up downstream from OCC. It’s a dramatic effect to the industry of how much smaller OCC we see today than we saw three to five years ago.

“Trying to recover as much of the smaller OCC as possible while not contaminating the OCC is the trick,” he adds. “We’ve made some developments there, and we’ve replaced some conventional screens in the marketplace that may still have wrapping issues.”

From there, Hawn notes that Machinex strongly believes in scalping the stream. By that he means separating the smaller containers and fiber from the OCC “unders” and diverting it straight to the finishing device, thus bypassing news screens.

“We’ve improved what we’ve taken out of OCC and smaller OCC in the beginning of the process, and then we try to minimize the amount of small or flat material that sometimes likes to travel with fiber on news screens,” says Hawn. “Now, we’ve cleaned up the stream before we used the machine. Now, the new screens could be more efficient with what we’re trying to separate from fiber and containers.”

On the sorting side of operations, Machinex believes in using optical units in combination with manual sorters. Hawn notes that the goal here is to remove the brown and light-weighted/flattened containers from the fiber.

“We’ve improved the quality of the fiber by taking the brown out and putting it with your existing OCC. It’s a win-win,” Hawn points out. “We are also ejecting the contaminant, so anything that could be metal or anything that could be plastic is getting blown out of the stream. What we’ve seen with the optics is we eliminate a lot of manual labor on the backside.”

AI, Infrared and Robotics

In order to complement some of the technologies companies are already using, some are turning to robotics to help sorting operations run more efficiently. And amid a growing labor shortage, robots could be beneficial. But are they the real answer to the widespread contamination problems?

MSS is working on AI and robotics now, but Hottenstein feels the technology is not quite good enough or fast enough yet. He projects that the technology will improve over time but says right now, the return on investment isn’t there from an operational standpoint. Plus, he says, robots take up quite a bit of space, especially in a retrofit situation.

“In general, the high-speed sorter can do up to 1,000 picks per minute of what it can sort out,” says Hottenstein. “A manual sorter, on average, does about 45 picks per minute over an eight-hour shift, which is 20 times as many picks as a human sorter.”

Infrared technology combined with color sensors and metal detectors in the high-speed sorters have been key to MSS’ offerings, according to Hottenstein. For instance, he says MRFs can add these optical sorters on each line and cut workers from the sort line, which could be considered a bonus amid an industrywide labor shortage.

“Obviously, the machine is never 100 percent, and there are always items that are too heavy for the air jets to move them; for instance, a full diaper makes it challenging,” he adds. “The machine does a good job, but it’s not perfect.”

On the container side of operations, Machinex is also building robots. Machinex’s SamurAI is designed to help minimize labor and set new goals for purity and efficiency. Right now, SamurAI is only available on the container side. Hawn notes that though it does have opportunities in other areas of the MRF, the company doesn’t want to go to market prematurely and misrepresent what the robot can do right now.

At the end of the day, Hawn feels the company’s ballistic separator becomes more of the best separation medium compared to disc screens. Like Hottenstein, Hawn also feels robotics will play a crucial role when it comes to labor shortage concerns across the country and throughout the industry.

“Robotics will never replace the optical sorter; they’re a good accompaniment to the optical sorter,” stresses Hawn.

For BHS, the company says its Max-AI technology is changing what is possible with MRF design and performance. Peter Raschio, marketing manager at BHS, says the technology allows MRFs to process better quality recyclables at a lower cost per ton. But BHS is also using detection technology for optical sorters and MRF intelligence, he points out.

“BHS’ NRT SpydIR with Max-AI is capable of detecting and ejecting material categories that were previously impossible using NIR,” adds Raschio. “Max-AI VIS sees what’s there similar to a person, but all of this data is recorded and available to operators in real time and trending.”

“This provides more information on material composition throughout a facility and can also be used to analyze product quality,” he continues. “A customer of ours in Oslo, Norway, is using Max-AI technology to automate their quality control positions and to also monitor end product quality.”

For Van Dyk, Neitzey also says high-speed optical sorting is a huge advantage when it comes to recognizing objects on the belt that normally would not have been recognized. Van Dyk has implemented near infrared sensors on its optical sorters as well. The company also provides metal sensing, laser object detection and color camera detection.

“It’s really about how the material is prepared to go underneath the scanner,” states Neitzey. “The scanner uses these four technologies and says, ‘that’s a drinking bottle, that’s a piece of cardboard, this is a piece of plastic,’ and then it decides what you want to eject by using an air bar that sends a signal to shoot a jet of air at the end of the conveyor.”

Neitzey also says that robots can play a role—but a very small role since a robot can grab only around 60 picks a minute.

“We have a robot, and we’re not anti-robot. But it is a small tool and just a piece of the puzzle. It doesn’t solve the problem,” he emphasizes. “Robots are a piece to the puzzle, and they play a role in final quality control of plastics. They play a role in final recovery on a last chance of a conveyor—like before material falls off and goes into the trash. But that is where I see it changing.”

For Van Dyk, the biggest advancement has been its non-wrapping screen. And Neitzey says a combination of technologies and leveraging optical sorters is what really needs to happen for every MRF.

“It’s not just about dropping in an optical sorter or a robot to solve all your problems,” adds Neitzey. “You have to go a little further back, and you have to size and prepare the material for the optical sorter to work properly. It is about presenting the material perfectly on a conveyer—everything single layered—to any optical sorter, and I feel like you do that using screening technology. But optical sorting in combination with screens is really the retrofit that needs to be done to ‘solve the China crisis.’”

The China Challenge and Moving Forward

Up until the China ban went into effect, MRFs were able to get rid of material even if it was really contaminated. Now, China has not only demanded but is strictly enforcing clean imports or nothing at all.

“China wants what they used to have, which is clean paper that doesn’t have bottles, cans or cardboard in it,” explains Neitzey. “It just doesn’t exist because no one reads the newspaper anymore. So now, by dilution, newspaper is less, cardboard is up and this film is wrapping around the technology, so it all carries over and you have a choice to make: You can put 25 people on it and have them grab 45 picks a minute, which would be the worst job in America. It’s hard to find workers to do that job. It’s hard to find workers that are good doing that job who want to get paid at minimum wage. So, that becomes an even bigger factor.”

A trend that BHS has seen is that operators are taking better care of their equipment from a maintenance perspective and running it within manufacturers’ specifications.

“We certainly see the trend of our customers working to clean up material to command the highest price possible,” says Miller. “Further, most are increasing fees to municipalities in providing the service to them.”

From his experience, Hottenstein points out that in the past, facilities would add more labor to their operations, slow the lines down and process lower throughput, so employees could manually sort better. But at some point, these facilities can’t put any more people on the line with an existing system because there isn’t enough space for them. So, something else must be done.

The key, according to Hottenstein, is pulling and leveraging data from the sorting technologies and aggregating it to make smart decisions for the operator. So, belt scales, for instance, will tell operators if they have too much or too little material on the belt.

“If you have that data, you can figure out how to make a smart decision and use the data to help the operator in real time, more or less,” emphasizes Hottenstein. “Using the data is key to help run your MRF better and smarter.”

Moving forward, Hottenstein thinks the technology is very close to working quite well, but what will happen is the MRFs will have to run at a slower volume and at lower throughputs to handle these new materials.

“If you run the same MRF at half the speed, your cost per ton doubles. So, the cost for sorting and processing the materials will increase no question,” he adds. “Again, it comes back to consumer education and counties and cities willing to pay more for recycling.”

And in the wake of China’s import restrictions, manufacturers have been reacting based on customer demand. However, as Hawn points out, reactions have been somewhat customer driven, but Machinex has been trying to stay as far in advance as it can.

“National Sword is a certainly situation, but the screen vents actually put us in motion,” says Hawn. “So, we weren’t caught off guard as bad by having to make technical developments because we were already focused on what the screen vents could do and how we could improve our process.”

“In the end, things happen in this market, but we always improve,” he adds. “I would say the industry as a whole in regard to cleaning residential, single stream materials has improved, and technology has helped significantly with that.”

But, as Hawn emphasizes, the industry always has to be looking forward. In the short term, he projects certain areas in the country won’t be accepting anymore residential, single stream material, which he says would be “horrible.” He expects to see a good bit of consolidation in the next few years.

“When you look at the stream and what we’re going to have to work with, there are rumors out there that Amazon is trying to become friendlier on the OCC and possibly change their packaging,” says Hawn. “We are watching to see if that happens. My concern is that it will become a less recyclable commodity than small OCC.”

But when it really comes down to it, the proper moves have to be made before materials are sent to the MRFs. And that’s something that has to happen at the consumer education and regulatory level.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like