Choreographed Chaos

Defining the role of waste management in recovering from human-made and natural disasters.

March 2, 2013

Michael Fickes, Contributing Writer

Between late 2006 and the end of 2007, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) issued enforcement actions against five landfills in and around New Orleans that received debris, construction and demolition materials and other refuse left in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Accusations included failing to keep records documenting the removal and disposal of unauthorized waste; failing to segregate unauthorized waste in separate containers; depositing waste without checking for unacceptable material such as paint, creosote, telephone poles and other banned materials; failing to lay down daily cover material; and a host of other actions long prohibited by landfill regulations.

atrina spawned disposal problems across the region. In eastern New Orleans the Almonaster Corridor, which has provided city residents and others with illegal trash and debris dumping opportunities for decades, became a magnet for Katrina debris.

atrina spawned disposal problems across the region. In eastern New Orleans the Almonaster Corridor, which has provided city residents and others with illegal trash and debris dumping opportunities for decades, became a magnet for Katrina debris.

Problems in the Corridor got so bad that in March and April of 2007 the LDEQ, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Corps of Engineers and the Louisiana National Guard mounted an operation called Cleansweep to put a stop to illegal dumping in the area and to close down a number of unpermitted facilities.

Funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the operation installed video cameras at illegal dumping sites throughout the corridor. The video surveillance led to inspections of all properties along a five-mile strip of the corridor. LDEQ’s enforcement division issued violations to 147 of 178 sites that were inspected. Many were related to Katrina.

By mid-May of 2008, LDEQ could point to 120 enforcement actions for violations related to the disposal of debris from Katrina. It’s a powerful example what happens when emergency planners fail to consider the massive needs for waste and debris removal that arise after a major disaster. It takes proper planning by local officials with reputable, knowledge- able and capable waste and recycling haulers and landfill operators to ensure the proper sorting and disposal of storm debris.

While emergency planners have been struggling to get disaster waste management right for decades, the increased frequency of extreme weather events is highlighting that need. In general, the terrorist attacks of 9-11, Hurricane Katrina, and most recently Superstorm Sandy have underlined the critical importance of competent waste management in recovering from a disaster.

The Massive Challenge Posed by Disaster Waste

“Massive” is the right word to use when talking about the volume and scope of debris generated by a disaster on the order of Katrina or Sandy. In fact, a human-made or natural disaster lasting just a few days can generate as much solid waste as a community normally produces in 15 years — this, according to a 2011 study published in “Waste Management: International Journal of Integrated Waste Management, Science and Technology.” A research team from the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand, investigating disaster waste management, published the study.

The study also cited a jaw-dropping FEMA figure: an estimated 27 percent of the disaster response funds spent during U.S. disasters occurring between 2002 and 2007 went to debris removal.

Disaster waste poses more problems than disposal, adds Charlotte O. Brown, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Civil and Natural Resources Engineering and the leader of the University of Canterbury research team. According to Brown, disaster waste blocks roads and hinders the work of first responders looking for survivors. It creates environmental problems and threatens human health.

A Simple Plan

In an effort to improve disaster response at all governmental levels, the federal government has produced a number of emergency planning documents. One that is available on the FEMA website is “Developing andMaintaining Emergency Operations Plans.” Local, state and federal emergency planners use this document or one like it to develop emergency operations plans (EOPs) that include waste management.

For example, the document advises planning officials to “describe the process used to identify private agencies/ contractors that will support resource management issues (e.g., waste haulers, spill contractors, landfill operators)."

Once identified, it suggests, planners should develop memorandums of agreement and contingency contracts with these organizations.

Once identified, it suggests, planners should develop memorandums of agreement and contingency contracts with these organizations.

“Emergency plans do consider debris and waste removal,” says John H. Campbell, operations chief with the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency from 2000-2011. “But these areas really don’t get the amount of pre-planning they deserve. When I worked in emergency management in Missouri, we focused a lot on debris.”

What Should Waste Companies Do?

“Today trash haulers and landfill operators should get to know local emergency management people,” says Campbell. “Depending on your size you might make local, or local and regional contacts. Developing relation- ships is a key element of pre-disaster preparations for planners.”

Emergency planners want to know who to turn to when the time comes, continues Campbell. So make these relationships and renew them regularly. In government things change constantly. People move up or on. Campbell says its wise to check in with emergency operations contacts every six to 12 months to see whether any new people have signed on.

Landfill operations, of course, always play a key role in disaster recovery. Landfill managers should stay in regular touch with emergency planners in the region. Websites for most state and local jurisdictions list an emergency planning office. Check with the director of that office.

When it comes to picking up vegetative debris, local jurisdictions typically turn to disaster clean-up specialists such as Willow Grove, Pa.-based Asplundh Tree Expert Co.

But there will be plenty of work for regular commercial and residential haulers. First, they will need to tend to the increased needs of regular customers. Second, they can help with the general cleanup by supplying and servicing roll-off containers.

Haulers may also help empty out temporary waste handling sites where collected debris is sorted and hauled to appropriate destinations.

The Joplin Tornado

How does all of this come together in an emergency?

In the spring of 2011, a giant, mile-wide tornado smashed head-on into the small city of Joplin, Mo., killing 158people and injuring more than 1,100. It was the deadliest tornado to strike in the United States since 1947.

The storm destroyed 3,500 houses and 500 business establishments. About 3,500 more houses and 400 more business establishments sustained damage.

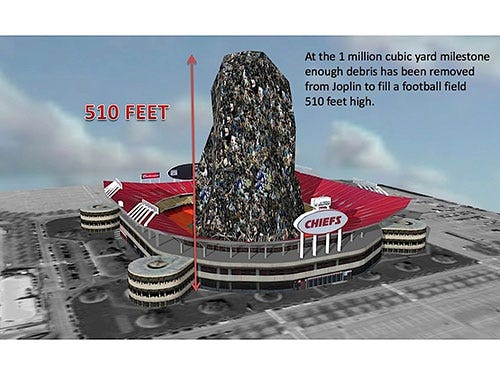

In its wake, the tornado left 3 million cubic yards of debris. “One million cubic yards of debris would fill Arrow- head Stadium (home of the Kansas City Chiefs) and go 500 feet over the top,” says Jack Schaller, assistant director of Public Works in Joplin. “We had to clean it all up within 65 days of the Presidential disaster decree.”

In its wake, the tornado left 3 million cubic yards of debris. “One million cubic yards of debris would fill Arrow- head Stadium (home of the Kansas City Chiefs) and go 500 feet over the top,” says Jack Schaller, assistant director of Public Works in Joplin. “We had to clean it all up within 65 days of the Presidential disaster decree.”

Why 65 days? When the President declares a disaster, federal and state emergency funds become available to pay the complete cost of the cleanup, explains Schaller. But officials want the work done efficiently and for the lowest possible cost. As an incentive to insure this, the funding — 90 percent from FEMA and 10 percent from the state emergency management agency — is available for 65 days following the disaster. After 65 days, the formula reverts to the normal funding ratio of

75 percent FEMA, 10 percent state and 15 percent local.

Still, was it possible to pick up and haul away three football-stadiums- worth of debris in 65 days?

Debris specialist, Knoxville, Tenn.- based Phillips & Jordan Inc., hit the ground running in Joplin, subcontract- ing with small and large companies with grapple trucks. “Thousands of grapple trucks follow these storms,” says Schaller. “Phillips & Jordan sub- contracted with the trucks, tracked the tickets and loads.”

The grapple trucks use claws to grab large volumes of debris that might include tree stumps, branches, white goods, furniture or virtually anything else a storm might stir up.

“We got most of it cleaned up within the 65 days,” says Schaller. “We did need a follow-up contract that the city administered to handle the leftover cleanup. The state helped pay for this with community development block grant funds. So while the cleanup wasn’t covered completely by federal and state funds, we minimized the costs.”

Joplin also minimized the illegal dumping that characterized the Katrina cleanup. “You have to investigate calls about illegal dumping,” Schaller says. “People don’t like illegal dumping, and they will report it. Most people try to do the right thing, but if you investigate a report of illegal dumping and find it to be accurate, you make the people that did it clean it up.”

Lessons Learned

“We are working to preposition a contract with a company that specializes in cleaning up storm debris before the next storm,” says Schaller. “Normally, a city has to advertise for a contractor. That takes 15 days. Then we have to present at a council meeting. It can take three weeks before we award the job. Then the contractor has to mobilize. That can take a month.”

Joplin didn’t have to go through that to start the tornado cleanup. The Army Corp of Engineers (ACE) coordinated the cleanup, and Joplin simply referred Phillips and Jordan to ACE. Schaller recommends the practice of referring suppliers to ACE, noting that ACE would then pay the supplier. If the city let the contract, then the city would have to pay the contractor and apply to be reimbursed.

Joplin didn’t have to go through that to start the tornado cleanup. The Army Corp of Engineers (ACE) coordinated the cleanup, and Joplin simply referred Phillips and Jordan to ACE. Schaller recommends the practice of referring suppliers to ACE, noting that ACE would then pay the supplier. If the city let the contract, then the city would have to pay the contractor and apply to be reimbursed.

But Joplin officials want to be sure that a debris specialist is prepositioned with a contract in the event that ACE isn’t around next time.

“We don’t specifically mention our local waste haulers in our emergency planning documents,” continues Schaller. “They can’t handle the vegetative debris produced by a tornado.”

Still, the local residential and commercial waste haulers have roles to play during emergencies.

Of the three million cubic yards of debris left by the Joplin tornado, grapple trucks contracted by Phillips and Jordan cleaned up about half. Citizens and regular residential and commercial waste haulers cleaned up the rest.

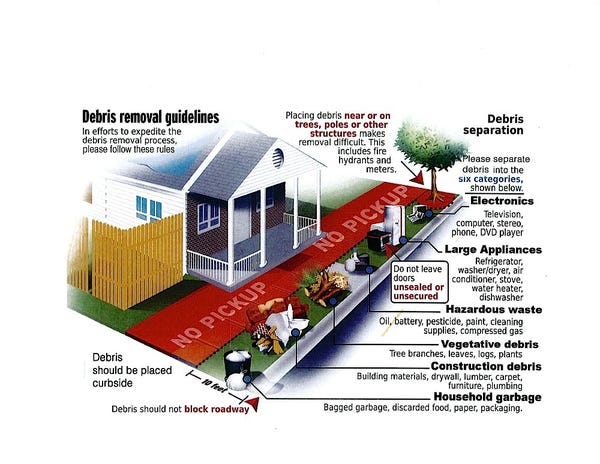

“We didn’t have many plastic bags,” Schaller says. “Residents separated the materials as best they could and put them on the curb.”

Contractors with backhoes and local waste haulers with roll-off trucks and containers picked up those materials.

“The incentive for our citizens and contractors and waste haulers to separate the material was that they got a cheaper rate at the landfill,” Schaller says. “Un-separated material is considered hazardous and the tipping fees are higher.”

Since 9-11 and Hurricane Katrina, the federal government has urged the states to develop EOPs for worst-case scenarios in their geographic region. The West Coast looks at earthquakes; Missouri and seven surrounding states also consider earthquakes. The New Madrid fault, a major earthquake fault line, runs through the region. “The idea is that if we can plan a response to a worst-case disaster, we can handle less serious problems,” Campbell says.

In light of the spike in extreme weather events that has occurred in recent years, it seems wise to institutionalize disaster planning — and to make disaster waste management a part of it.

Michael Fickes is a Westminster, Md.- based contributing writer.

You May Also Like