Colorado Explores Compost to Cut GHGs, Jump-start Agriculture

Stakeholders in Colorado are looking at composting, among other methods, to sequester carbon to achieve farming and environmental benefits.

Several years ago, researchers in Marin County, Calif., found that compost applied to soil can sequester carbon from the atmosphere, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while feeding soil and nourishing plants. Now, stakeholders in Colorado are looking at composting, among other methods, to sequester carbon to achieve the same farming and environmental benefits.

A Boulder County study found compost to be most effective of several carbon sequestration techniques in that region. And an experiment on a degenerated city-owned agriculture plot also is showing that compost seems to effectively sequester carbon and jump-start vegetation.

But what works in one region may not work in another.

“We need to test on different landscapes and different climates to know compost’s potential there. Plus, at about $73 per metric ton of carbon sequestered, compost is among the most expensive sequestration methods trialed. And that’s a tough bullet to bite,” says Brandon Welch, director of Carbon Economy for Mad Agriculture, an organization dedicated to regenerative farming practices, which create agriculture systems that mimic natural cycles of the earth.

Eco-Cycle and a coalition of environmental and agriculture groups are trying to get funding in Colorado to assess various soil-building practices that sequester carbon, including composting.

“We are doing a business plan with districts of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) to show how we will implement these practices and to let them know the cost that NRCS could help defray,” says Dan Matsch, director of the compost department and center for hard to recycle materials at Eco-Cycle. “We are trialing applications working with NRCS local district offices so the agency can determine if they want to go statewide.”

The coalition Matsch is working with is also looking to engage the public to create data showing potential for carbon sequestration on urban soil.

“We hope to get families interested in doing projects in their backyards or with their church or school. Then, we would test to see if there is a difference in carbon in the soil, post-trial,” he says.

There is market demand for compost in California as the state works to meet the goals of SB 1383 diversion. California has set up incentive programs, sharing costs with farmers to implement practices, including composting to sequester carbon.

The state also offers incentives to compost producers. But funding for both programs will need to increase in order to meet California’s carbon sequestration goals, says Calla Rose Ostrander, strategic advisor for People, Food and Land Foundation, which focuses on expanding carbon sequestration in California.

Ostrander worked with the Marin Carbon project, which conducted a survey that found many sites in that region had more carbon in the soil than others—some up to 10 times more. Sites with the highest carbon content had received manure applications.

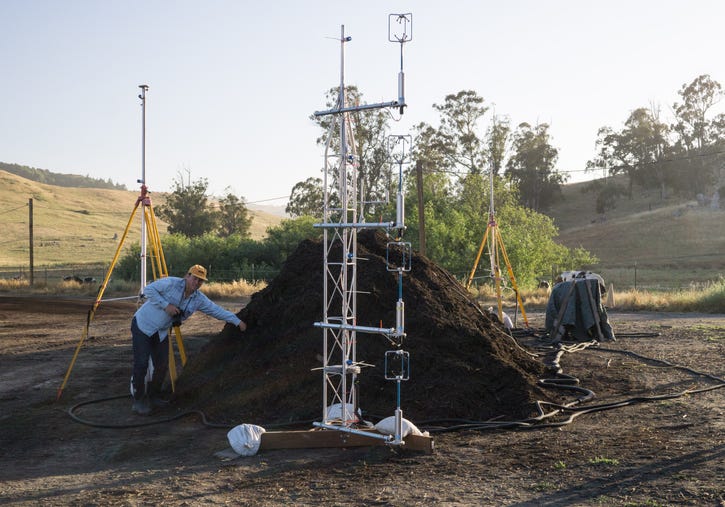

Researchers looked to determine if applying carbon-containing compost to soil surface (instead of manure) would create a long-term carbon sink, which is an area where carbon is absorbed and stored.

“Unlike manure, finished compost has no carbon emissions or pathogens. Plus, the nitrogen has been stabilized, so you get a slow release fertilizer,” says Ostrander.

The study found that, where compost was applied, 1 to 3 net tons of carbon were gained per roughly half acre over 12 months. Another ton to 2 tons of carbon entered each plot over five years, without adding compost.

McCauley Family Farms is working on a carbon sequestration project on agriculture property owned by the city of Boulder that’s degenerated to the point that it’s unleasable.

“We can’t sequester carbon on bare ground, so we first had to generate pastures by harvesting water and rotating animals who fertilize the ground. Then, we compost,” says Marcus McCauley, farm manager for McCauley Family Farms.

On the plot where McCauley is testing, he found compost, paired with a subsoil plowing technique called keyline, seems to be the most effective pasture regeneration and carbon sequestration strategy.

“I think this method sequesters carbon because in areas where we keylined and composted, we have seen plant growth where there had been no plants at all,” says McCauley.

He will be taking soil and plant samples to further determine success of techniques.

“The more carbon you sequester, the more plants you can grow and, ultimately, we hope to reduce carbon emissions. So, we can feed people with more nutrient-dense food while nourishing the planet by sequestering carbon,” says McCauley.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like