Oregon Works Toward a Modern, Resilient Recycling System

The state has developed a Recycling Steering Committee, which expects to recommend changes for a more resilient recycling system by summer or early fall.

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and its partners are working together through a recently developed Recycling Steering Committee to update and modernize the state’s recycling system, which was heavily disrupted in 2017 after international markets began restricting acceptance of many materials.

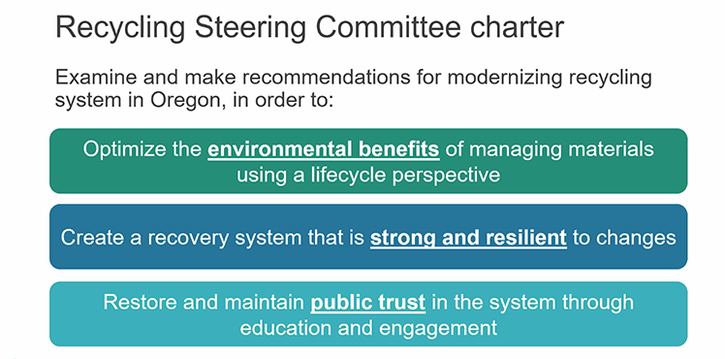

The Recycling Steering Committee convened in 2018 to examine the recycling system and make recommendations for modernizing that system to optimize environmental benefits, manage disposal, fund a resilient system and restore public trust. DEQ brought together players responsible for Oregon’s recycling system, including local and state governments, businesses and other organizations, through the Recycling Steering Committee. The work is supported by Oregon Consensus, a program of Portland State University and the National Policy Consensus Center.

The Recycling Steering Committee has been working with DEQ to identify what Oregon’s future recycling system should look like, conduct research to inform decisions and—by summer—recommend changes to achieve that future system. On January 31, the committee held an information session titled “Oregon’s Future Recycling System: Info Session about Potential Options” that discussed the committee’s most up-to-date research, as well as five potential framework scenarios developed in collaboration with consultant Resource Recycling Systems (RRS).

Looking at Oregon’s Current Recycling System

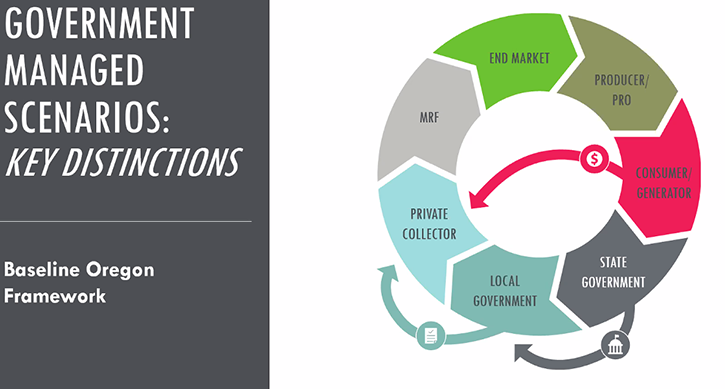

The Opportunity to Recycle Act and the 2050 Vision and Framework for Action provide the policy framework for Oregon’s current recycling system. The system relies mainly on local governments for program design, ratepayers to fund the system and private companies for service provision, service (including processing fees) and a reasonable rate of return. These rates include a franchise or license fee (typically between 3 and 7 percent) paid to the city or county franchisor.

Disruptions in international markets for the materials collected for recycling have affected Oregon’s ability to recycle in nearly all parts of the state. In response to the market disruptions, some local recycling programs have removed items that are no longer cost effective for them to recycle, increased garbage and recycling service rates to cover increased costs, or both. These changes have increased awareness of the state’s recycling practices and signaled that it is time to update and modernize Oregon’s recycling system, according to DEQ.

Oregon does not regulate the processing and marketing of materials, as those activities are governed by the open market. Most of the state is served by six materials recovery facilities (MRFs) in the Portland area, one in the Salem area and one in Vancouver, Wash. Despite many recent challenges with markets, a few of Oregon’s MRFs have made significant investments in sorting technology over the past two years.

Even with commodity values at remarkably low levels, Oregon MRFs have continued to deliver materials to domestic and foreign end markets, according to DEQ. Oregon also has a bottle bill, which recovers a higher percentage of materials and generates a cleaner outgoing stream than other collection systems. Beverage distributors are legally responsible for operating the bottle bill system.

However, recycling policy in Oregon dictates that cities with populations more than 4,000 are required to provide what is referred to as “the opportunity to recycle.” That opportunity includes collection of recyclables from households and businesses, but only when the cost to collect and transport recyclables is lower than the cost to transport the same materials and send them off for disposal.

“Oregon’s recycling policies were created decades ago under very different circumstances. The recent collapse of global recycling markets made the shortcomings of our system more apparent, so we have a generational opportunity to modernize and improve Oregon’s recycling system,” explained Steering Committee Chairman David Allaway, who is a senior policy analyst in the materials management program at Oregon DEQ.

“Fixing some of the problems of the recycling system will cost more money, but under our existing laws, if recycling costs more, local governments are not required to collect as many materials,” he added. “This creates a strong tension between material quantities and the quality of the programs.”

Another major problem is that processors often work to remove contamination, but sometimes the economics work against them. And producers, such as brand owners, design materials that hamper the recycling process and include misleading labels around claims of recyclability that further add to contamination.

“As we work to improve the recycling system, we also need to keep in mind the importance and limitations of recycling. Our current use of materials is not sustainable,” said Allaway. “Even if we recycled every last piece of scrap from across the state, our use of materials would be less impactful but still not sustainable. So, we need recycling, but we need additional solutions in parallel. We need to be using less material overall.”

An additional challenge, emphasized Allaway, is how to modernize recycling in a way that simultaneously addresses these bigger concerns or at least doesn’t make them harder to solve. Take, for example, the growing enthusiasm to mandate that all packaging be recyclable. While this would help the recycling system, sometimes that format has higher environmental impacts because of how products are made, he explained.

“We need to keep our higher order goals in mind, front and center, and remember that recycling is a means to an end and not the solution by itself,” Allaway pointed out. “All of these challenges have been building for some time. They came into sharper focus in late 2017 when China imposed its policy National Sword. Oregon, which had come to rely heavily on Chinese markets, was hit hard.”

Working with RRS to Develop Framework Scenarios

The Recycling Steering Committee has been working with RRS to develop framework scenarios that the Steering Committee will evaluate further.

“These five scenarios are not the only possible task forward. They are not a ballot. And one of the five candidates will not emerge as the potential victor,” stressed Allaway. “There are thousands of ways to combine different kinds of policies and program elements. I would like to encourage you to think of these five scenarios as broad prototypes, essential directions that have been designed to deepen our understanding of the option before us.”

The committee will continue to explore those options in subsequent meetings, with evaluation of detailed infrastructure scenarios scheduled for later this spring. Both will converge this summer, and then there will be a final consensus and implementation planning. The committee hopes to have its final recommendations by early fall and then get to work on a shared path forward.

“It is very likely that some of the recommendations will provide changes to statute. We are expecting legislative activity on this topic in 2021,” noted Allaway.

During the January 31 information session, Resa Dimino, a senior consultant for RRS, provided a deeper look at the five scenarios that the committee will consider.

Scenario 1: Enhanced Government Managed—Oregon would have increased responsibility and authority to implement and enforce new program elements, such as parallel access to recycling collection (where waste is collected), a common statewide list of mandatory recyclables and universal volume-based pricing of solid waste collection. MRFs would be subject to a certification or permitting program and reporting standards. Lifecycle assessment results would be integrated into end-of-life decision making, a multi-stakeholder Recycling Advisory Committee would be established and there would be increased investment in infrastructure and end market development. Additional funding would be required.

Scenario 2: Enhanced State Managed with MRF Contracts—This includes all elements of Scenario 1. In addition, DEQ would enter into contracts with MRFs to allow collection service providers to deliver materials, pay no gate fee and receive a reimbursement for transportation costs. Additional legislation would be required to facilitate the contract terms necessary for this scenario to be practical (e.g., to allow for DEQ expenditure at a level greater than the current legislated limit, and/or to coordinate material flows). Significant additional funding would be required.

Scenario 3: Post-Collection Producer Responsibility—Local governments would continue to manage recycling collection programs to meet state obligations, while the producers of designated recyclable materials would be required to manage and finance transportation, processing and marketing of residential and commercially generated recyclables, as well as necessary recycling infrastructure investments. Producers would also be responsible for financing litter abatement and waste reduction/prevention and upstream activities. Processors would contract with and be funded by producers and be subject to state certification or permitting. Producers would likely meet their obligations by funding and participating in a producer responsibility organization (PRO). Fees into the PRO(s) would be based on a formula, informed by DEQ research that incentivizes design for environment considerations (known as eco-modulation).

Scenario 4: Producer Responsibility with Local Control—Producers would be required to manage and finance the post-collection part of the system; finance litter abatement and waste reduction/prevention and upstream activities, just as in Scenario 3; and be financially responsible for recycling collection programs. Collection would continue to be managed by local governments, but ratepayers would no longer pay for those costs. Instead, program costs would be reimbursed by producers. Processors would contract with and be funded by producers and be subject to state certification or permitting. Obligations would likely be managed by a PRO(s) and would be funded through eco-modulated fees.

Scenario 5: Full Producer Responsibility with Optional Local Involvement—Producers would be required to finance and manage the recycling system, including public education, collection, transportation, processing and marketing of recyclables, as well as necessary recycling infrastructure investments.

Producers also would be responsible for funding litter abatement and waste reduction/prevention and upstream activities. Producers would likely work through a PRO(s) to implement the program through a series of contractual arrangements with collectors and MRFs. Processors would contract with and be funded by producers and be subject to state certification or permitting. Local governments would no longer have operational responsibility, although they could choose to serve as collectors, through a contract with the PRO(s), in order to maintain a role in the system, if desired. In this case, they would likely subcontract to a private collector. Local governments could also choose to opt out of the program altogether, which would result in operating as status quo with no funding received from the PRO(s).

The committee plans to reconvene at the end of February to discuss its parallel recycling infrastructure research. Then, the committee plans to explore further questions and solutions to rebuild the state’s recycling framework in subsequent meetings.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like