Landfill Operators Aiming for 100-year Sites

Long-term planners rely on collecting good data and leveraging the technology they have, while keeping an eye on emerging technologies.

Some landfill operators are aiming to keep their facilities going for 100 years—or longer—and they have ideas for how to do it.

But there are caveats to planning that far into the future. Among them are the inevitable, such as changing waste streams and new rules and regulations. And from a technology perspective, an operation is only as good as its engineering design, equipment and systems options.

Long-term planners rely on collecting good data, following trends and leveraging what technology they have, while keeping an eye on emerging technologies. Then, there’s some educated guesswork involved.

With its existing fill rate, Monterey Peninsula Landfill in California, which has operated since the 1960s, has sufficient capacity to last another 120 years.

“What’s unique to our county is we had a government agency with good foresight. It secured 500 acres more than 50 years ago in a well-located area with the right land use [agriculture and range],” says Tim Flanagan, Monterey Regional Waste Management District general manager.

The site had a few hundred feet of cover material and an underlying, naturally occurring clay liner, which checked off a lot of boxes, unbeknownst to them.

“But there’s no magic engineering button; it’s having elected officials, policymakers and waste staff that support policies in the present that will benefit folks beyond their immediate tenure,” says Flanagan.

The most important metric to evaluate in planning in advance is remaining yards or tons of capacity, and then to look at how much is landfilled each year.

“We can only gauge by tons per compacted cubic yard to tell how much airspace we have left. So, the effort to estimate years [versus tons] is a little ingenuous. You could quadruple your waste in a given time, or, conversely, it could go down,” says Flanagan.

Key to staying on top without having a formula to determine number of years left, and key to dealing with changing streams, changing regulations, among other unpredictables, is doing long-term strategic planning and staying current on trends, he adds.

Delaware built three lined landfills between 1980 and 1985.

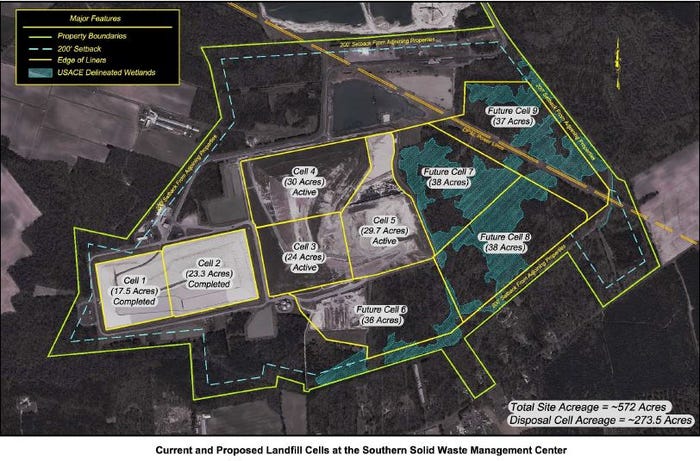

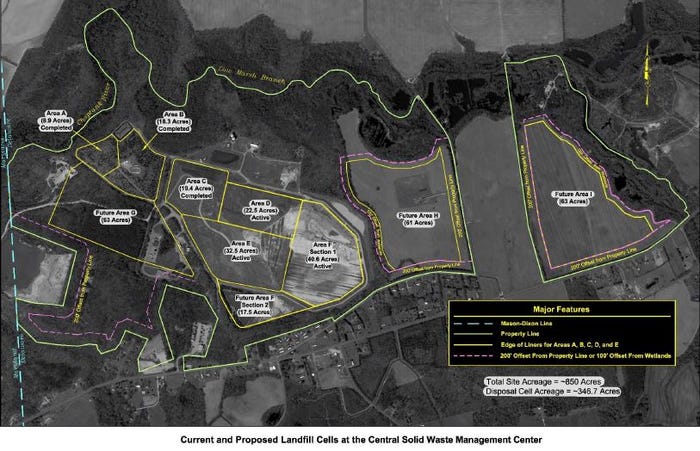

While each facility is currently approved for only the existing cells, each site is designed to go beyond when those cells would be expected to be filled. One landfill is designed to last another 50 years, one to last 73 years and one to operate for the next 98 years.

Still, the ultimate goal is for each landfill to take in waste indefinitely. But even by updating plans every 10 years and making future projections as you go, you can’t always know what the future holds, points out Rick Watson, CEO of the Delaware Solid Waste Authority. So, the authority has taken a proactive stand to control what it can.

Strategies have involved acquiring adjacent properties for future use, adopting techniques like compaction and reducing cover and implementing engineering improvements like installing drains to strengthen soil to be able to build higher.

Designing sites and systems with the ultimate goal to run indefinitely has entailed riding learning curves, especially around recycling.

In the 1990s, 185 recycling drop-off sites were established throughout Delaware, each with about nine bins for various streams.

“We learned we needed to simplify the system. It wasn’t getting the targeted percentage of recyclables. And we had issues with collection costs and traffic, as we had trucks going to 185 sites that each picked up different materials,” says Watson.

The authority added a voluntary curbside, five-stream system, and when that proved complicated and expensive, it switched to single stream.

It went on to maximize its single stream system in 2010 by requiring haulers to pick up recycling. Then, in 2012, the authority launched a materials recovery facility (MRF), which kept 95,000 tons of the state’s would-be waste out of the landfills this past fiscal year. A co-located construction and demolition facility manages this special, bulky waste to save more space.

Key to longevity will be new, economical processing technologies such as landfill mining, believes Watson.

“By digging up materials, we think we can get back 30 percent of cell space from reusable cover soil alone, and then free more space by recovering metals,” he says.

Flanagan is also optimistic about the potential of evolving technologies and systems. More importantly, he says people’s will to be more environmentally responsible will advance, too.

“When I started in this industry, there weren’t more than about two dozen curbside recycling programs in the whole country,” says Flanagan. “Curbside recycling is all over now, and people want to be environmentally responsible, which will help us keep going.”

“In truth, if you ask me how long our landfill could last, if we do it right, it should last into perpetuity,” he adds.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like