Adam Minter shares insight from his new book, Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale

June 18, 2020

What happens to the clothes donated to thrift stores that aren’t sold? What about clothes and textiles not good enough for resale, where do they go? Adam Minter, author “Junkyard Planet” and a journalist for Bloomberg, explores these questions and more in his book, “Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale.”

Secondhand takes readers on a global journey, deep diving into the industry of reuse. It was also chosen as the first book to kick off Waste360’s new Book Club which held its first live discussion on June 11.

Minter gave a live presentation delivering insight on how he put together some of the ideas in the book that was several years in the making, starting with a photo tour of the process of producing shoddy wool.

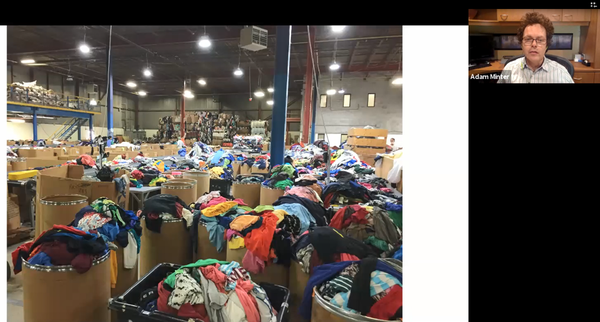

“This is a used clothing warehouse in Mississauga, Ontario. If you read the book, you’ll know that Mississauga is one of the hearts of the global clothing trade. What they do there is they basically bring in used clothing from Goodwill, Salvation Army, and thrift shops from all over North America, sort them, then send them on to markets around the world where the clothes can be reused,” said Minter.

When the clothing gets to the sorting part of the process the sorting goes beyond separating into shirts, pants, dresses, it’s sorted by color or in other ways specific to the local market that it’s being resold to, he said.

“It’s an incredibly sophisticated process that requires an enormous amount of knowledge about the local markets,” said Minter.

While observing the sorting process, Minter said he noticed that most of the countries that receive used clothing are warm-wet climates and most of the donated items come from cold weather climates like North America and Europe.

“So, I started wondering, what happens to the wool?” asked Minter. “Nobody in Banin or very few people are going to be interested in used wool sweaters.”

This thought put Minter on a quest where he found that he isn’t the first person to wonder what happens to wool.

“This was an old problem and an old industry,” said Minter.

He said he found that back in the early 19th century there was a lot of used wool that no one wanted so Benjamin Law in 1813 in England invented a machine that chopped up wool that was made into a type of material called shoddy.

“Shoddy is wool. It’s a very low-quality wool. It’s cheap and it was highly favored during the American Civil War,” he said. “It was hot, scratchy and uncomfortable but it was something they could afford because most of the union soldiers were expected to purchase their own uniforms so they would do it on the cheap.”

Shoddy gained popularity around the world and by World War II Prato, Italy, became known for its shoddy wool production until the 1970s when it became too expensive to produce in Italy and production was moved to Panipat, India, said Minter.

“At the pinnacle of the Panipat-Shoddy trade there were around 600 factories of significant size importing shoddy from all over the world” he said.

That number has since dropped but factories still collect used clothes, sort them into various piles and move out of the warehouse to be further processed. Women use blades to remove zippers, buttons and anything else that can get caught in a machine, he said.

And what happens to the buttons and zippers and materials removed? They get sold to other people who sort out the buttons by type and sell them back to the manufactures to be used again, said Minter.

“Here’s a great circular economy story. I know everybody in Europe and the United States is trying to invent the circular economy; one of the messages of my book and really my work the last 20 years is it’s already been invented. This fellow takes those buttons, sorts them and then sells them to new garment manufacturers, and they’re sewn on to new garments and nobody knows the difference,” said Minter. “He’s a very important part of the circular economy that exists in India and Panipat.”

Once the material is all sorted and processed it gets put through a machine that essentially turns the shoddy into a mulch which is then fed through a spinning mill to produce a thread.

“The thing to know about shoddy thread is it’s shoddy! That terms comes from something. When we refer to something as being ‘shoddy good’s’ it means it’s not very good. It’s made from used wool, has very low thread count, somewhere in the range of 10-13 threads. The garments they make aren’t very pleasant. They can’t hold a lot of color, can’t be woven into interesting patterns. They’re worn, scratchy and even when washed they have a damp smell. But that hasn’t stopped anyone from turning them into garments and it shouldn’t,” said Minter.

Today, instead of war uniforms shoddy is used for blankets.

“The reason shoddy was so successful in India for so many years was not because it was a ‘poor man’s’ blanket. What Panipat built its reputation on was making something called a relief blanket,” said Minter.

Organizations like Red Cross deliver relief blankets made almost 100 percent of shoddy wool from Panipat, India because the blankets were cheap and factories could produce up to 40,000 blankets per month, he said. But in recent years shoddy blankets are dropping in popularity due to warmer winter seasons, an improving economy where people can afford better quality blankets and polar fleece blankets became more affordable to produce.

Minter said the cost of producing polar fleece blankets was around $7 per blanket and shoddy blankets cost around $2 but in recent years China has been able to drop the price of fleece blankets to around $2 while also producing more quantities at a faster rate. He said people just also prefer the feeling of polar fleece.

Factories in Panipat and others saw the change in the market from shoddy blankets to fleece blankets so some manufacturers went to China to learn the process and brought it back with them to produce fleece blankets in India, he said.

“So what does that mean for wool clothing?” asked Minter. The demand for wool has significantly dropped and “that’s a problem on a number of levels. One, we don’t know what to do with all that wool clothing at this point. And two, if you care about the environment you probably know polar fleece is not a recyclable fabric.”

“For me in writing this book and tracing it out to the very end it was very interesting to me and also very depressing because I couldn’t come up with an answer on what happens next, I certainly found out where some of this wool is going but nobody knows what’s really going to happen to all this excess wool now that polar fleece has taken over the relief blanket trade” said Minter. “That’s sort of the sad but fascinating story about shoddy I wanted to share with you today.”

Following his presentation about shoddy the discussion opened up to a Q&A.

What might be the new material to knock polar fleece out?

Minter: I’ve asked around about that and nobody knows yet. Polar fleece is still on the ascent. As you saw, you have these factories going in and it’s become such an easy thing to make as long as you have access to the cheap petrochemicals and everybody does now. You can make a lot of it for very little. So the incentive to develop alternatives to polar fleece is very low.

What has changed in the secondhand market since COVID-19?

Minter: The global markets for secondhand are completely out of whack right now. In two ways. One on the supply side- if you drive by a Goodwill or Salvation Army in North America this weekend I guarantee you cars will be lined up, lines that can go as long as an hour and that means there is a flood of stuff coming in people did their COVID spring cleaning. So you’re creating a supply glutton.

Meanwhile as we all know if we’re in the trade it’s becoming very hard to get containers. Countries that are destinations for recyclable and secondhand, their economy has slowed down too so there’s less demand and you’re seeing prices really collapse. Some of this is starting to move a little bit but right now the whole trade is in a little bit of stasis. It reflects other commodity industries. Remember maybe a month to six weeks ago stories about oil being held in giant tanker ships offshore because no one was buying it but it was still being accumulated? Well, it’s kind of the same situation with a lot of secondhand especially in the global markets right now.

What do you think is more relevant to the waste stream right now? Textiles or electronics?

Minter: Unabashedly I’d say textiles if you’re concern is volume. The volume of textiles that are being consumed every year dwarfs the volume of electronics by magnitude. There’s no comparison. If you’re just interested with what’s going to be filling up landfills and incinerators by volume it’s got to be textiles. I know the follow up to that is the toxicity involved with electronics and I’m very mindful but there’s also toxicity involved with textile as well and manufacturing of textile. And its just in different forms. I think we’re all familiar with the microplastic phenomenon and manufacturing of polar fleece near open bodies of water contribute an enormous amount of plastic into the ocean stream so I would argue textiles need to be addressed soon.

What surprised you the most in all your travels while writing this book?

Minter: Very general answer to this. This book was reported all over the world- Africa to Japan to Southeast Asia and all over North America and thing surprised me the most wasn’t a single revelation, it was scale. How much stuff is coming out to people’s homes, how much stuff Is in people’s homes. The sheer volume of it. it dawned on me kind of slowly but really congealed when I was spending time with companies in Japan and US who go and clean out homes and help people downsize home. And we all think there's always going to be some Goodwill that wants that; there's always somebody on eBay who’s going to buy it. And there often is but more often than not there’s more stuff than anybody can possibly consume and I saw that up close and personal both in homes and warehouses and hearing it from companies that we don’t know what to do with all this stuff.

Any country doing this well or who isn’t as focused on consumerism?

Minter: No is my solid answer. I mean I think it changes though I mean I think society and economies go through cycles you know and I mean I wouldn't want to overplay it but I think you do see more mindful consumers in North America and Europe – again, I don't want to overstate that because there's extraordinary amounts of consumption going on-- but on the other hand these emerging economies they want their chance to consume, they want their chance to have that lifestyle that we have. I live in Malaysia when I'm not sheltering from COVID-19 in Minnesota and you know in Malaysia I mean consumption is you know is a big part of how people enjoy their leisure time and that’s something we do in this country and still do so I don’t think we’re really at a point where we see mass movements to reign that in yet.

Are you seeing any brands that you’re impressed with whether they’re reusing recyclables or plastics?

Minter: I think there's a model coming about and I think there's a couple brands that are doing it and it's starting out small as all good things do but I think it's very hopeful at least in a couple sectors. The model is the used car model, basically, and that is you buy something and everybody who buys a new car has in the back of their mind, “what will I be able to trade it in for in three, four, five years or whatever many years it is from now?” You always have that resale value that quality in it and we’re starting to see this happen in different sectors of the consumer economy.

You know I'm sure there's folks listening who are involved in phones and secondhand electronics and we all know that Apple now you can literally trade in a phone and in the process is quicker but it's not all that much different than the model that new and used car dealerships have enjoyed and profited from for years and we're starting to see this with textiles as well. Patagonia is now accepting trade-ins of its clothing, Patagonia clothing, that they will then give you credit for and you could buy new. Meanwhile they'll take that used Patagonian clothing, wash it, make sure it's in decent shape and they are selling it in their stores. The idea is similar to what a car dealership says, “You know that Patagonia pullover is very expensive, the new one, for say a college student but we can at least get him into the brand with this nice used one.” That's the used car model, and so I think there's other companies doing it but just off the top of my head as we talk about it right now, Apple and Patagonia are the ones that stand out so I think that's a very interesting model I think we'll see more of that.

How would you create a system that best uses textiles at the highest value?

Minter: Well that’s a big question that I don't know. I didn't really come up with an answer for that in the book but I think I think Patagonia is thinking the right way and I think there are a couple of things that we could do. I think we all know, and I get into this a lot in the book, is you know they don't make things like they used to.

I suggested in my book a voluntary labeling system that gives people a sense of how long the fabrics they’re buying will last so that they can make good informed choices as consumers that doesn't even need to be about the environment they just say you know instead of buying that shirt that's going to only last five washes I'll take the one that will last 50 and pay more for it and I think if you empower consumers with knowledge I think that's how you start getting better outcomes.

All of us in the waste and recycling industry, what can we do?

Minter: I’m really interested in the textile question right now. I was really shocked by the volume. I think we all know that we've heard the stories for years about fast fashion and disposable fashion but I don't think we've heard that much talk actually coming from the waste of recycling industry that in many cases is going to be getting it. Of course we all think in the back of our minds, oh Goodwill handles it, Salvation Army handles it, but I'm sure there's people on this call that are like, “Oh yeah we pick up from Goodwill and Salvation Army, stuff that they can't market. I think it needs to start being talked about. I mean I think if we've learned anything on the recycling side over the last five to 10 years is that perhaps we all, and I include myself in this because I'm a recycling journalist, we all sort of failed to educate the public as well as we should have about the true nature of the industry and how it is very market dependent and I think it's good to start talking about these issues now because they really are going to come to a head.

In the book I found it fascinating how different countries have different attitudes about secondhand goods. Did travels and conversations change your perspective on the role of secondhand goods?

Minter: I found that fascinating, too. It’s one of the most enjoyable and interesting parts of doing this book is talking to people and seeing how they viewed it within their cultural context. The answer is yes, writing this book changed a lot for me and for my family. I've never been a big shopper, I'm not somebody who buys a lot of stuff and that noted, like anybody who lives in contemporary America, contemporary Malaysia, or China or wherever it is, I consume and there’s stuff just piling up and I hold on to books and things and what really changed me and I think it changed my wife's outlook, I don't want to speak for her, but we would talk about this book as I was writing it every night and look at my reporting and she’d see the pictures. What really changes us was the experience of going to home cleanouts in Japan and the United States and with these cleanouts they’re maybe downsizing their home or moving to senior living or maybe after somebody passed away you need a professional to come in and help you decide what to keep from mom and dad’s stuff or whatever it is. These are incredibly painful events to watch and be a part of. I’m talking from my perspective, not even from the family’s perspective, I’ve been through two of them in the last few years and then to go in as a journalist and watching from afar and see how hard it is for people to let go of the life’s accumulation.

Seeing that happen in multiple cultures specifically Japan in the United States made a huge impression. We just started buying less stuff. That’s what it ultimately came down to. We just started buying less stuff. We started thinking more intentionally about the stuff we’re buying, buying better quality stuff. I bought some training wheels for my son for his bicycle I looked into buying secondhand I couldn’t, but you know they were sort of two options you buy the cheap one or buy the better one. I bought the better one, I figured he's going to use them for a couple of weeks and then some other kid is going to use them and that's kind of how I go about my shopping at this point and it's partly it's just because I don't want to leave a garage or closet full stuff so that's sort of how it changed us.

Consumers tell pollsters they want to buy recycle and be sustainable but purchasing behavior betrays that. What will take consumers to do what they say will do?

Minter: I thought about this a lot and thought I’d have to come up with an answer for the book and I sort of just gave the answer and I think it’ll be more part of it. I think the boomers are retiring, they’re downsizing, some are passing along. You’re going to see the great North American clean out and the need to sort of have a reckoning with a generation’s stuff.

What I saw in Japan and the United States tells me you’re going to see people thinking more seriously because of what’s happening generationally.

Where do you think data in the recycle textile supply chain could have the most value?

Minter: The thing about the recycle textile supply chain especially since coming out of thrift stores is it's changing very rapidly now because the quality is declining. One of the things in the thrift stores especially the charity based ones that don't like to talk about is that more and more stuff is getting diverted to landfills because nobody is going to buy it; they won't buy it domestically, they won't buy it internationally; you can't dump stuff internationally, if you ever could. Everybody has the same social media, they know what folks are wearing in London they know what a good quality garment is and they don't want the cheap garment. I wished when I was writing the book I actually could find data that would show that more and more of this stuff going into thrift stores is just not resalable secondhand. Boy would I love to have that data point that starts ticking upward showing that more and more of the stuff going into the thrift stores just cannot be sold. Somebody would have to work with the thrift stores, Salvation Army, Goodwill or whatever it is and they would be probably reluctant to share that data because people get very emotional when they hear that their clothes are not good enough to be resold and sorry you know you bought it at Forever 21 and it’s forever now in the landfill. But I think that kind of data point could be extremely potent if somebody could put it together.

Will or should the sorting communities begin forming in the US. Will that make a difference?

Minter: The most important thing from my perspective when you're looking at sort of donor countries like we are, we sell as well, but l I think we really need to be focused on improving quality and giving people the knowledge to buy better quality garments and encouraging the purchase of better quality. The sorters that you find in thrift stores, I've been talking about the ones in Benin, you know some of the most joyful reporting I've ever done was sitting on a stool in the sorting rooms at Goodwills in Tucson with the clothing stores and just listening to them talk through what they see and how things are changing and they would show me scenes and it's just wonderful.

I don't think you necessarily need to layer on top of them because there's a pretty good job being done in the sorting room right now I think the real effort needs to be getting people to think more seriously about quality.

What is advice you have for people cleaning out right now?

Minter: The first and most important thing right now is to hold off donating, go ahead and clean up but right now the thrift stores are just swamped. It's not that they don't want your stuff, they want the stuff and they want to sell it but if you can hold off, like they got more than they can handle. Wait another month or two so that the great rush is over -- that's number one. But by all means, clean out. And two, if you look at something and you say nobody is going to use this, don’t donate it. I don't want to sound like a snob but I spent a lot of time sitting on a stool at the donation doors of Goodwill’s and watching what comes through and it was really frustrating to see the amount of garbage, literally garbage, that comes through the doors at a Goodwill, so give them your good stuff because what they end up doing with your stuff, and I talk about this book, they're there to make a profit from it but they are nonprofit and they do amazing job training programs and youth interventions. The charitable side of Google is an extraordinary thing and if you're giving them junk then they need to pay probably somebody on this call to dispose of that junk and it becomes a cost and then they could do less job training for people so when you look at that stuff make sure that you're giving them good stuff that they can use and the rest of it you know it's sort of your obligation to pay for the disposal, not theirs.

You May Also Like